PHYSICIAN LEADERS AND SELF-COACHING:

4 KEY QUESTIONS

Joy Goldman, RN, MS, PCC, and Petra Platzer, PhD, ACC

In this article…

Walk through two scenarios in which physician leaders were uncertain in their

positions and were coached through four steps to clarify their roles and authority.

IN TODAY’S INCREASINGLY COMPLEX HEALTH

care environment, many physician leaders are finding themselves

in new roles or looking for ways to be more effective

in their current positions. Health care is in a period of

transformational change that is raising the bar for health care

leadership skills, particularly in the area of managing complexity

and ambiguity.

What does this mean for you, the physician leader?

In our experience as executive coaches partnering with

physician leaders in health care, we have identified a common

developmental theme: how to let go of the way you

learned to lead as a provider and shift into a different way

of leading that better prepares you for this transformational

change. In seeing many similarities among their challenges

with this, we feel compelled to provide a tool to accelerate

this process for you.

OUTCOME ➡ ACTUAL ➡ RESEARCH ➡ STEP

O.A.R.S. is a four-question series that will effectively and

consistently navigate you toward success in your day-to-day

and strategic operations.

Meet Dr. Smith, a successful surgeon with over 25 years’

experience at the same organization. Smith was just named

chair of her division and found herself part of a much larger

system as her organization completed merging with several

other hospitals.

“No one else was stepping up and with all the changes the

department has been going through, I knew I could provide a

stabilizing force,” she said. “I’m used to feeling very confident

and have doubted myself as I need to manage behavioral issues

with my former peers, negotiate contracts and establish

policies. I know administration is asking me to step up and

represent them while I’m also being challenged to advocate

for those who are still my peers in the clinical world. I have

no idea how to manage all of that!”

DOES THIS SOUND FAMILIAR? — Now meet Dr. Jones, a

seasoned leader serving for several years at the C-level in a

hospital system. Having previously shifted from provider to

leader, Jones is now finding himself challenged with being

able to make decisions effectively and moving forward quickly

while working with physicians and leaders in different groups

with different priorities.

Although he appreciates the need for collaboration and

communication, he is often frustrated with the lack of control

he feels to just get it done and having to continue to talk with

people until everyone understands. He recognizes that when

working across departments, these people will not become direct

reports. He is frustrated and unsure how to get the results

the organization needs in such a matrixed role and system.

These cases represent two common paths we find with

emerging and seasoned physician leaders. Although the context

and details are all unique, there is a meta-thread: recognizing

a real level of frustration and wanting to learn how to

get a different result. This recognition is a critical first step

to getting that different result. The next steps are to put the

“O.A.R.S.” in the water and navigate toward that ultimate

vision. To begin using O.A.R.S., follow this process:

STEP 1: WHAT OUTCOME DO YOU WANT?

Smith answers this question with what she doesn’t want

— “I don’t want to be stuck in meetings all day and I don’t

want to be dealing with conflict all of the time.”

Jones responds that he wants to be more effective.

Have you found yourself seeking similar types of outcomes?

Interestingly, neither state a clear result toward which one can

create goals and action steps. Having a clear desired outcome

is the first step in being able to achieve it.1

For example, unless you are clear that “I want a balanced

life,” your success at achieving this is at risk. It is also at risk

if you hold this as a goal versus outcome; an outcome is the

result of goals. By defining the outcome, you can create specific

action steps (goals) toward achieving it.

Achieving a goal of dropping your cholesterol, for example,

doesn’t mean you have achieved a healthy cardiovascular system.

The last and perhaps unfamiliar part of answering this

question is to focus on what you want as an outcome, versus

what you don’t want. There is much evidence that focusing

on “I want more sleep” results in more success than when

focusing on “I don’t want to be tired.”2

In the case of Smith, as a coach, we would ask: “Instead

of focusing on what you don’t want, there was a reason you

chose to step in and take this role. What was it you wanted to

be able to accomplish as chair?” For her, it was her desire to

lead the division toward excellence in quality care and provider

and patient satisfaction.

For Jones, in hearing he wants to be effective, an additional

question to get a more concrete outcome is to ask: “What

result would that give you and others?”

Once you define your outcome, you are ready for the next

step in O.A.R.S..

STEP 2: WHAT IS YOU ACTUAL STATUS NOW? — You must

be honest about finding your actual status. Perform your own

diagnostic, in an objective way, on the elements needed for

that outcome. In the cases of Smith and Jones, their selfassessments

ring true for many of our physician leaders.

Smith was flattered that the organization asked her to be

chair, but struggled with having new administrative and strategic

responsibilities. “I’m thankful, but I don’t really know

how to contribute. I’m used to having the answers and feeling

competent in my role. I don’t feel that way here.”

Jones felt unsure of himself and frustrated. What had

worked for him to get where he was no longer was working.

“I was focused on implementing the changes, and the physicians

have gotten on board with what’s needed. Now I am

supposed to help set the strategy and bring it to the C-suite

but they don’t see me in that kind of way yet.”

In doing this self-assessment, they importantly identify

strengths, a sense of what’s working, as well as what is getting

in their way and not working for them. A common thread

is they are dealing with new layers of complexity that require

different competencies than those learned in medical school.

There are more players to talk to for decision-making, and

networking can take a long time. For many physicians who

are used to people executing their orders, this delay — and

what can seem like superfluous work — is frustrating. They

are left knowing that what once worked for them isn’t working

that well now and are unsure how to develop these new

competencies to be successful.

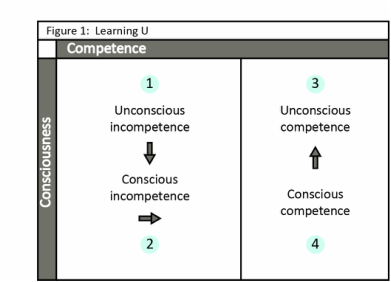

At this stage, we actively move into quadrant 2 of the

Learning U. This learning theory model, adapted from the Conscious

Competence Ladder,3 has helped our clients recognize

and understand where they are in their learning process for

the new competencies needed for their outcomes.

4 KEY QUESTIONS

Joy Goldman, RN, MS, PCC, and Petra Platzer, PhD, ACC

In this article…

Walk through two scenarios in which physician leaders were uncertain in their

positions and were coached through four steps to clarify their roles and authority.

IN TODAY’S INCREASINGLY COMPLEX HEALTH

care environment, many physician leaders are finding themselves

in new roles or looking for ways to be more effective

in their current positions. Health care is in a period of

transformational change that is raising the bar for health care

leadership skills, particularly in the area of managing complexity

and ambiguity.

What does this mean for you, the physician leader?

In our experience as executive coaches partnering with

physician leaders in health care, we have identified a common

developmental theme: how to let go of the way you

learned to lead as a provider and shift into a different way

of leading that better prepares you for this transformational

change. In seeing many similarities among their challenges

with this, we feel compelled to provide a tool to accelerate

this process for you.

OUTCOME ➡ ACTUAL ➡ RESEARCH ➡ STEP

O.A.R.S. is a four-question series that will effectively and

consistently navigate you toward success in your day-to-day

and strategic operations.

Meet Dr. Smith, a successful surgeon with over 25 years’

experience at the same organization. Smith was just named

chair of her division and found herself part of a much larger

system as her organization completed merging with several

other hospitals.

“No one else was stepping up and with all the changes the

department has been going through, I knew I could provide a

stabilizing force,” she said. “I’m used to feeling very confident

and have doubted myself as I need to manage behavioral issues

with my former peers, negotiate contracts and establish

policies. I know administration is asking me to step up and

represent them while I’m also being challenged to advocate

for those who are still my peers in the clinical world. I have

no idea how to manage all of that!”

DOES THIS SOUND FAMILIAR? — Now meet Dr. Jones, a

seasoned leader serving for several years at the C-level in a

hospital system. Having previously shifted from provider to

leader, Jones is now finding himself challenged with being

able to make decisions effectively and moving forward quickly

while working with physicians and leaders in different groups

with different priorities.

Although he appreciates the need for collaboration and

communication, he is often frustrated with the lack of control

he feels to just get it done and having to continue to talk with

people until everyone understands. He recognizes that when

working across departments, these people will not become direct

reports. He is frustrated and unsure how to get the results

the organization needs in such a matrixed role and system.

These cases represent two common paths we find with

emerging and seasoned physician leaders. Although the context

and details are all unique, there is a meta-thread: recognizing

a real level of frustration and wanting to learn how to

get a different result. This recognition is a critical first step

to getting that different result. The next steps are to put the

“O.A.R.S.” in the water and navigate toward that ultimate

vision. To begin using O.A.R.S., follow this process:

STEP 1: WHAT OUTCOME DO YOU WANT?

Smith answers this question with what she doesn’t want

— “I don’t want to be stuck in meetings all day and I don’t

want to be dealing with conflict all of the time.”

Jones responds that he wants to be more effective.

Have you found yourself seeking similar types of outcomes?

Interestingly, neither state a clear result toward which one can

create goals and action steps. Having a clear desired outcome

is the first step in being able to achieve it.1

For example, unless you are clear that “I want a balanced

life,” your success at achieving this is at risk. It is also at risk

if you hold this as a goal versus outcome; an outcome is the

result of goals. By defining the outcome, you can create specific

action steps (goals) toward achieving it.

Achieving a goal of dropping your cholesterol, for example,

doesn’t mean you have achieved a healthy cardiovascular system.

The last and perhaps unfamiliar part of answering this

question is to focus on what you want as an outcome, versus

what you don’t want. There is much evidence that focusing

on “I want more sleep” results in more success than when

focusing on “I don’t want to be tired.”2

In the case of Smith, as a coach, we would ask: “Instead

of focusing on what you don’t want, there was a reason you

chose to step in and take this role. What was it you wanted to

be able to accomplish as chair?” For her, it was her desire to

lead the division toward excellence in quality care and provider

and patient satisfaction.

For Jones, in hearing he wants to be effective, an additional

question to get a more concrete outcome is to ask: “What

result would that give you and others?”

Once you define your outcome, you are ready for the next

step in O.A.R.S..

STEP 2: WHAT IS YOU ACTUAL STATUS NOW? — You must

be honest about finding your actual status. Perform your own

diagnostic, in an objective way, on the elements needed for

that outcome. In the cases of Smith and Jones, their selfassessments

ring true for many of our physician leaders.

Smith was flattered that the organization asked her to be

chair, but struggled with having new administrative and strategic

responsibilities. “I’m thankful, but I don’t really know

how to contribute. I’m used to having the answers and feeling

competent in my role. I don’t feel that way here.”

Jones felt unsure of himself and frustrated. What had

worked for him to get where he was no longer was working.

“I was focused on implementing the changes, and the physicians

have gotten on board with what’s needed. Now I am

supposed to help set the strategy and bring it to the C-suite

but they don’t see me in that kind of way yet.”

In doing this self-assessment, they importantly identify

strengths, a sense of what’s working, as well as what is getting

in their way and not working for them. A common thread

is they are dealing with new layers of complexity that require

different competencies than those learned in medical school.

There are more players to talk to for decision-making, and

networking can take a long time. For many physicians who

are used to people executing their orders, this delay — and

what can seem like superfluous work — is frustrating. They

are left knowing that what once worked for them isn’t working

that well now and are unsure how to develop these new

competencies to be successful.

At this stage, we actively move into quadrant 2 of the

Learning U. This learning theory model, adapted from the Conscious

Competence Ladder,3 has helped our clients recognize

and understand where they are in their learning process for

the new competencies needed for their outcomes.

|

For Smith and Jones, while looking at their actual status

in relation to the outcomes they want, they saw that their frustration and confusion stemmed from the shift from feeling competent in what they had already achieved to now feeling less competent in what they were looking to achieve in their futures. Questions we asked Smith included: “What has helped you learn in the past? How did you deal with feeling less competent and still have people depend on you? How might you extend that same approach and compassion to yourself now?" For Jones, we ask: “What feels different to you in working with those in the C-Suite to leaders who you have worked with in the past? What assumptions might you be making?” For many, recognizing this model — and where they are in it — provides an added acceptance that what they are experiencing is a natural and expected part of this learning. And yes,it is less comfortable than what they are already familiar with. While doing this, remember to also have the confidence and belief that you have gone through this learning process before. This recognition and acknowledgement of your actual status in relation to your outcome prepares you to go to step 3 in O.A.R.S. STEP 3: WHAT RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IS NEEDED? — This step can be the turning point in your navigation. Here you are checking in on your willingness to really look in the mirror and, most often, accept that there are things you will need to learn and do in order to get to the result you want. On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is this to you? Are you able to be open to feedback as valid data to help you grow? Smith rated the importance of effective leadership driving quality and engagement as a 10. However, she was not used to getting the direct, constructive feedback she was getting now and it made her afraid she was letting people down. “I get yelled at by my physician peers and get complaints from administration. How can I feel successful?” Jones said this was a 9 for him. He shared that he’d done one or two assessments before but didn’t find them very useful. He realized that while he thinks of himself as open, he really only listens to people that he either respects or who have proven themselves to him. Jones was interested in doing a self-assessment but hesitated about doing a 360 because he had seen some colleagues struggle with the results they received. What has been your experience in assessing yourself and getting feedback? Most physicians’ training has been about perfection and mastery to be successful. For physicians transitioning into leadership roles, this trained level of expertise can sometimes be a barrier to trying something new in order to move forward in their Learning U. We also have seen this mindset create real challenges for clients when receiving feedback around their new leadership roles where their competencies are not yet strong. A helpful perspective for many is that in order to learn and grow as a leader, gathering current data is helpful — albeit not always comfortable. One difference now is that you are working with behavioral competencies, which take experimentation to develop. Amy Edmondson, in her book: Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy, talks about the evidence-based benefits of “failing fast.” Her application within health care might help you as you explore this new territory. In preparing Smith for her feedback, we asked: “When you assess a patient, you are curious about what’s happening with them; how can you apply that curiosity to your own experience?” “How are you allowing room for your mistakes Physician Leadership Journal 57 in service to your learning?” “What self judgments might youhave that get in the way of moving forward?” To help Jones be open to asking for feedback as a source of valuable data for his learning and growing, we shared that feedback is merely a snapshot in time of the impact you have on others through your interactions. We also asked him: “What was your motivation when you provided feedback to your colleagues on their 360 leadership survey? What are the benefits of learning your strengths and developmental opportunities from other people’s perspective?” After gauging your readiness to do research and development on yourself, you are ready for the final step in O.A.R.S. STEP 4: WHAT NEXT STEP ARE YOU GOING TO TAKE? This is the most tactical of the four steps. Once you know where you want to go, where you are now, and what data you are willing to access to get there, you are able to chart your course on these waters. Be sure to start with a realistic step you can take (we cannot make other people do things), in a specific timeframe, with a measurable result. Through this process, Smith recognized her reluctance to engage in conflict discussions and, with support, was able to more quickly address disruptive behavior. She had courageous conversations and was pleased that, regardless of the person’s reaction, she held true to what she knew was the right thing to do. Her behavior became less about people liking her, and more about taking the right action to support quality standards. Jones decided his next step was to do a 360 survey and a self-assessment. He proceeded with gathering feedback for his own leadership style and was pleased to see what he already knew and found a few areas he had not seen. By developing these relational areas along with his task strengths, he was able to lead more via influence than direct authority and made noticeable strides in creating the outcomes he wanted. He feels more confident in embracing the unknown to achieve the outcomes he defines using the O.A.R.S. process. This is making him a more effective leader in driving strategy collaboratively. In summary, although many habits you’ve honed as a clinician can serve you well as you take on a leadership role and more scope, they are not sufficient. Identifying those habits that support your success, and letting go of those that don’t, can help you perform better during this time of ambiguity and complexity.

REFERENCES:

1. Emerald, D. The Power of TED (The Empowerment Dynamic) Glendale, CA: Polaris Publishing, Oct 15, 2009 2. Cramer, K. and Wasiak, H. Change the Way You See Everything through Asset-Based Thinking. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press, Mar 1, 2006 3. Gordon Training International. Learning a New Skill is Easier Said than Done. http://www.gordontraining.com/free-workplace-articles/learning-anewskill-is-easier-said-than-done/. |